Originally published by the Clifton Courier, December 15

We have very precise ways of measuring time, but that doesn’t mean we’re all that precise about it in practice.

I mean, I often like to jokingly chime that “time is just a social construct, mahn!” but, at the same time, there’s no denying that time, you know, goes by. And the social construct of time and the shared understanding we all have of it is what keeps this society of ours ticking along in at least a somewhat orderly fashion.

We humans no longer have to rely on the rooster’s first crow or the curlew’s evening call to be a marker of time (although there’s some romance to meeting your secret lover just beyond the tree line after the evening birdsong sounds, it would be quite another thing to try to schedule a doctor’s appointment around that).

We’ve got these sweet new gizmos called clocks.

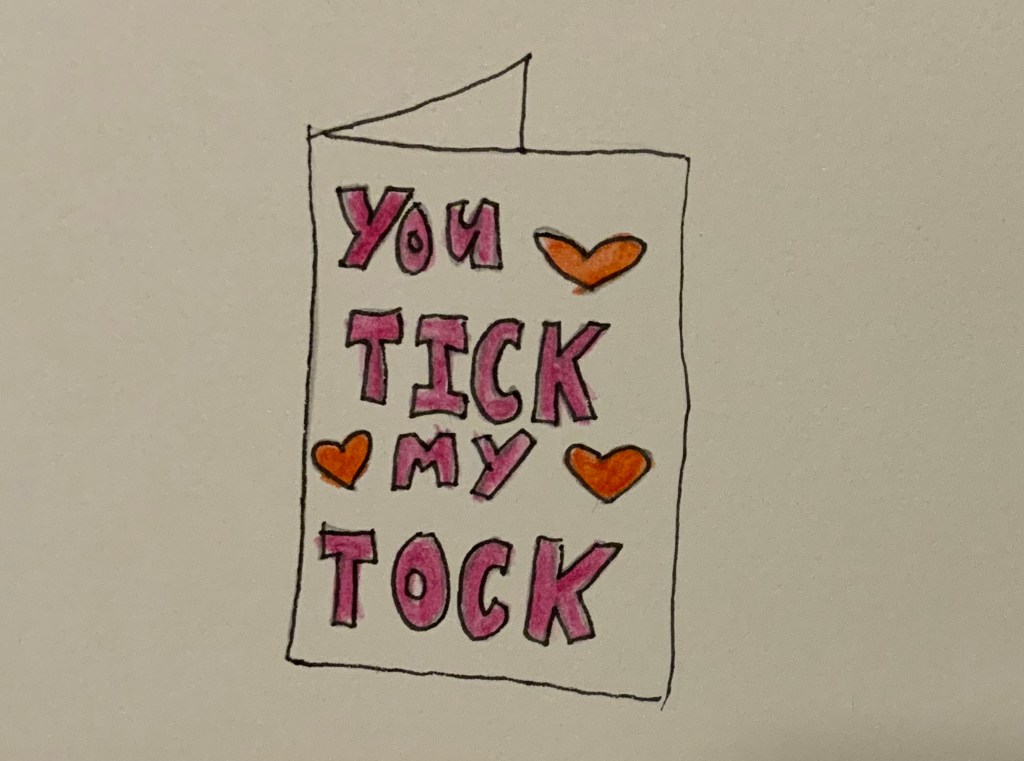

And while they now come in many forms – the grandfather clock that’s too heavy to move, a smartwatch and a microwave clock that you’re too lazy to synchronise but you know how many hours ahead it is so you do some quick maths to get a rough idea of the time (not that I’m speaking from experience or anything…) – we all generally tick to the same tock, if you catch my drift.

But just because we’ve got clocks, doesn’t mean this whole shared concept of time runs like clockwork. That only happens when we’re all clear on what time a specific time actually is.

Obviously when someone says “seven o’clock”, we all know what that means.

But when you’re a little looser with your language, it no longer comes down to the standard increments of seconds, minutes and hours, it comes down to individual assumptions and expectations. And we’re not always ticking and tocking in tune on that front.

For example, the other day I received a message from a friend advising me about a meeting which required my attendance.

The exact wording of the message was “PSA. Bowls club this afternoon 4ish”.

I’d received that message at 2.41pm, shortly after I’d finished work for the day. I decided that timeframe would give me enough time to get home, put on a load of washing, have a quick nap and trot on over.

Because, to me, “4ish” is a very fluid term. And, when I think about it now, it’s all about context.

If it were a “4ish” on a Monday afternoon in early February at a fancy venue that gets busy quickly and requires a reservation, I’d have applied a much tighter window of time around 4pm in which I’d arrive.

But because it was a Sunday afternoon in the pointy end of the year at a bowls club where people walk around with no shoes on and there’s always a seat, I thought the window was much, much wider.

There was no set time by which I had to arrive, so I felt that whenever I rocked up would be the right time. Not early, not late, but roughly just on time.

So I didn’t set myself an exact time I was aiming to arrive by. I’d just turn up when I turned up, I thought. I didn’t expect to be the first person there, but I wasn’t expecting to be the last either.

When I did turn up, five people were already there, some of them onto their second beers. One person had already ordered a round of calamari rings.

And the sender of the “4ish” message raised the question about what “4ish” actually meant to people. She wanted to know what we thought was an acceptable time for someone to turn up either side of the hour the “ish” was applied to. She wanted specifics.

One person said “ish” covered half-an-hour before and an hour after the hour in question.

Another said ten minutes before and ten minutes after.

Another said there was no time before, because otherwise they’d say something like “turn up a bit before 4pm”

Forced to get specific, I said it was half-an-hour before or half-an-hour after.

I hadn’t taken note of the time it was when I arrived, so I assumed that my appearance fell into my window of acceptability.

Turns out I walked in at 4.33pm, so I was officially late.